Okimono in shape of an Egyptian

Netsuke belong to the finest of Japanese carving art. The small “buttons” were used to attach pouches and pipes to the belt of the kimono. In the Meiji period, the traditional garment went out of fashion. Men were required to wear suits in public.

After netsuke largely lost their function, carving artists began to look for other outlets. This ivory okimono is reminiscent of a Christian Madonna figure. However, the veil and bead make it clear that this is a fellachin, an Egyptian peasant woman. The “fellachin” was an Orientalist motif of the time. It circulated, for example, in photographs taken by the Cairo photo studio Lehnert&Landrock. There were however no real peasant women sitting as models in Cairo, but prostitutes or actresses dressed as peasant wome

Fellah Woman with Niqab

Orientalism liked to make use of photography, which was still in its infancy at the time. This gave its fantasy worlds at least the appearance of objectivity. The Lehnert&Landrock photo studio in Cairo proved to be particularly influential. Around 1900, Rudolf Lehnert traveled to North Africa to photograph landscapes and iconic sites (such as the pyramids of Giza). In addition, he photographed people. Lehnert’s camera view combines ethnographic observation with a colonial gaze and erotic mystifications. This is also the case here. It is unclear who is behind the veil. It was often actresses or prostitutes who mimed certain “types” such as the “fellachin” (Egyptian peasant woman).

Statuette of an Egyptian

This “Egyptian” turns out to be French on closer inspection. The little curls that spill out from under the headscarf give her away. That was the fashion in Paris at the time.

Joséphine

It is said that Napoleon brought Josephine a precious cashmere scarf from the Egyptian campaign. All of Paris was delighted and a new fashion hype was born.

Hyakusenkai Graph (百選会 呉服催事カタログ資料 「百選会グラフ」大阪店発行)

One of the first department stores in Japan was “Takashimaya” with branches in Kyoto, Osaka and Tokyo. The management maintained close contacts with fashion scouts in the western metropolises. The female clientele was to be supplied with the latest trends. This kimono pattern probably goes back to the European “Egyptomania”.

Isis with the Child Horus

Sun Ra

Sun Ra (1914 – 93) was one of the most important African-American jazz musicians. At the same time, he was a walking Gesamtkunstwerk (a synthesis of the arts) who sought to elude identitarian attributions, starting with his name. The idea that his artistic freedom could be limited from the outside was anathema to him, and so he justified his musical mission with a visit to Saturn, where the extraterrestrials had instructed him accordingly. As a pioneer of Afrofuturism, Sun Ra took science fiction into his aesthetic service as well as elements of a pre-colonial imagination, and here in particular the high culture of ancient Egypt which the Afrocentrists revered as an African antiquity.

Empire coffee set with Egyptian decor

The decipherment of the hieroglyphs by Jean-François Champollion is one of the lasting achievements of Napoleon’s Egyptian campaign. But even Champollion would have cut his teeth on this Neapolitan sphinx.

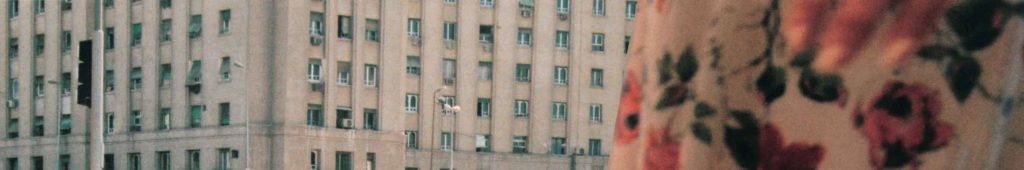

Maha Maamoun

Maha Maamoun: Cairoscapes – Untitled #1 & Untitled #5, 2003

C-Print

Courtesy of Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg

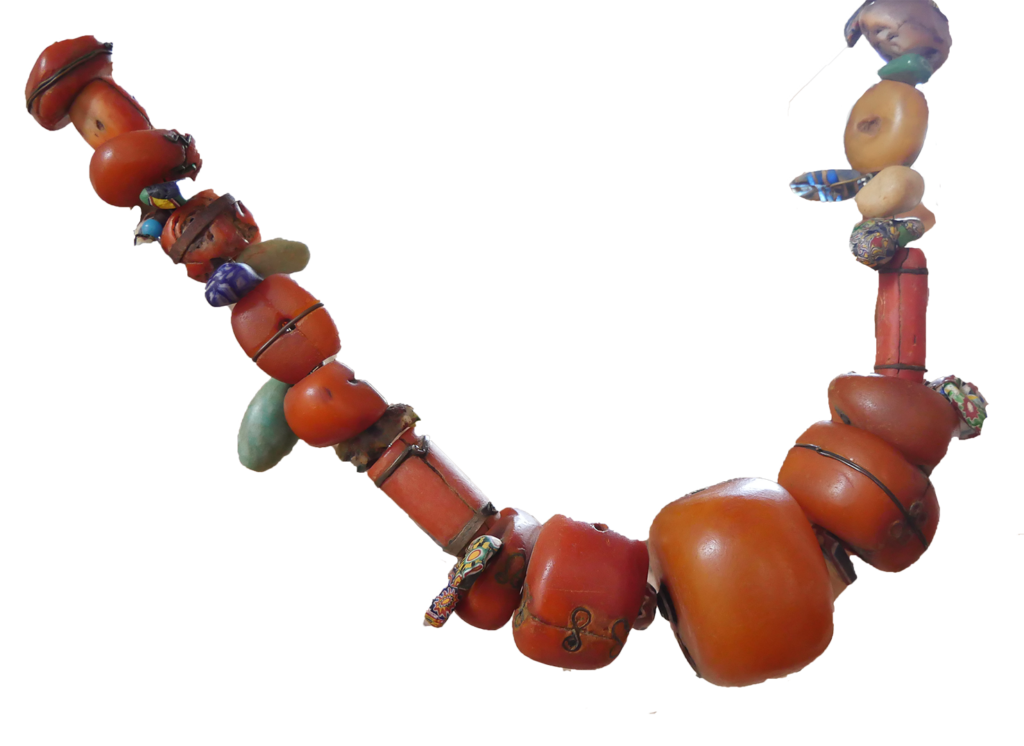

Reticello glass

For centuries, even before the Portuguese, Dutch, English and French, Venice had dominated global maritime trade and also provided the currency with which they traded: glass beads.

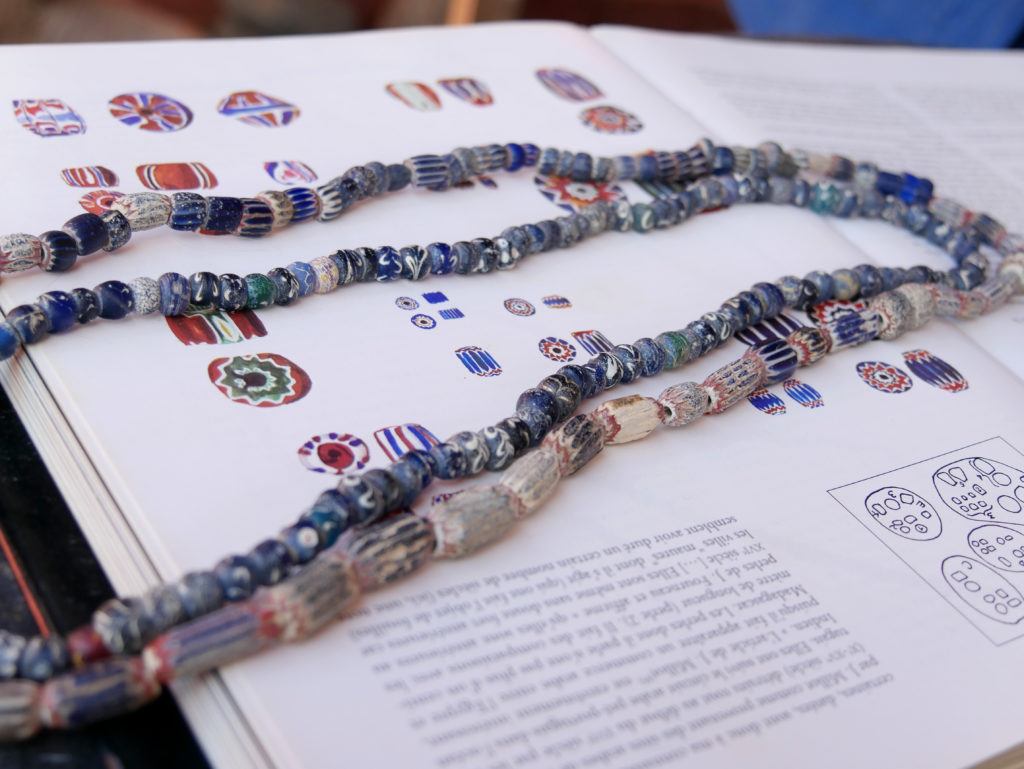

Marie-José Crespin

The so-called “chevron” beads we show here in a necklace by Marie-José Crespin served as currency in the West African slave trade. Crespin found them years ago in the sands of Gorée Island (Senegal), where the enslaved were gathered before being sent on the infamous “middle passage” (from Africa to the Americas).

Marie-José Crespin: Necklaces fashioned out of trade beads (no date given)

Courtesy the artist

Abdoulaye Konaté

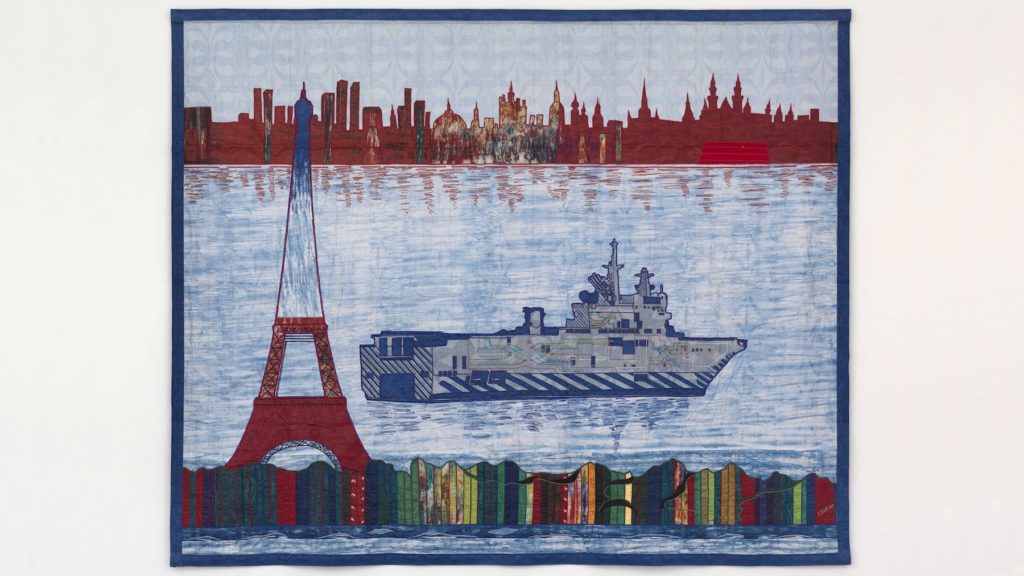

Abdoulaye Konaté: Mistral – Technology, Money and Politics, 2015

Textile

Courtesy Blain Southern, London/Berlin

Buoy with barnacles

What at first looks like a modern sculpture, turns out to be a buoy (made of Styrofoam) upon closer inspection. Besides its purpose, this buoy fulfills another function: it forms the home of countless barnacles. Barnacles are not just any animal, but have made history. On the one hand, they inspired Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution. For another, they could decide the race for global naval supremacy between England and France. As one can see from the buoy, the barnacle has no mercy for surfaces that lie under water. It attaches itself with a kind of cement to just about anything, be it rocks, ship hulls or even buoys. The cement can hardly be loosened. Ships infested by the barnacle lie deeper in the water and become increasingly unmaneuverable – a particularly devastating fate for warships and merchant vessels.

Clever Britons, however, came up with an antidote early on: Copper fittings. Toxic copper oxide deters the barnacle. The buoy is a souvenir of Charles Lim Ye Yong. It comes from Singapore, the tiny city-state at the entrance to the Strait of Malacca, the main shipping passage between Asia and Europe. Singapore is a colonial foundation of the British.

When the »Münsterland« returned

The return of the “Münsterland”: cheerful tooting of ship’s horns welcomed the freighters “Nordwind” and “Münsterland” in the port of Hamburg. For eight years, the two ships and their crews had been stuck in the Suez Canal.

Crab from Muranoglas

It was not only shipping that benefited from the construction of the Suez Canal. Fish, snails and mollusks suddenly got the chance to leave their ancestral biotope. Some crossed the canal forever. The small hermit crab from Murano is merely metaphorically related to the “Lessepsian migration”. A Venetian glassblower is currently working on a collection of all those sea creatures that migrated at that time. (The relationship between Venetian glass art and global maritime trade is a separate topic).