The Krull Brothers

The Krull brothers live in a small village in the northeast of Brazil. This village bears the speaking name “Helvécia”. The Krulls are descendants of Peter (Pedro) Peycke, a Hamburg merchant co-founded a colony of coffee plantations in Bahia 200 years ago. The required capital came from Swiss investors. The colony was called “Leopoldina” (in honor of the Empress of Brazil and Queen of Portugal, Maria Leopoldine of Austria). While Peycke was acting as consul of Hamburg in Salvador da Bahia, his nephews took care of the administration of the plantation. The profits were enormous. Although slavery was officially forbidden, documents prove the ownership of 125 enslaved people.

For more information on “Leopoldina”, see also the exhibition Coffee from Helvécia, curated by Marcelo Rezende and Eduardo Simantob.

Dom Smaz: Black Helvetia, Helvécia, Bahia, Brazil 2015-2018

Series of photographs

Courtesy the artist

“Indian lovers”

The cheerful scene in the courtly ambience throws a spotlight on the global imagination around 1750: the lute and chessboard come from the Arab world, the coffee in the cup from Africa or the Caribbean, the parrot from South America. The “Indian” flowers on the woman’s dress are from Japan, just as the garb of the two in general makes one think of kimonos and East Asia. When this sculpture was formed, the transatlantic triangular trade was in full swing. Are the enormous privileges enjoyed by the lovers to be regarded naively? In other words, what else would need to be shown next to the rococo sculpture for the whole picture to emerge?

Clutch bag with a parrot

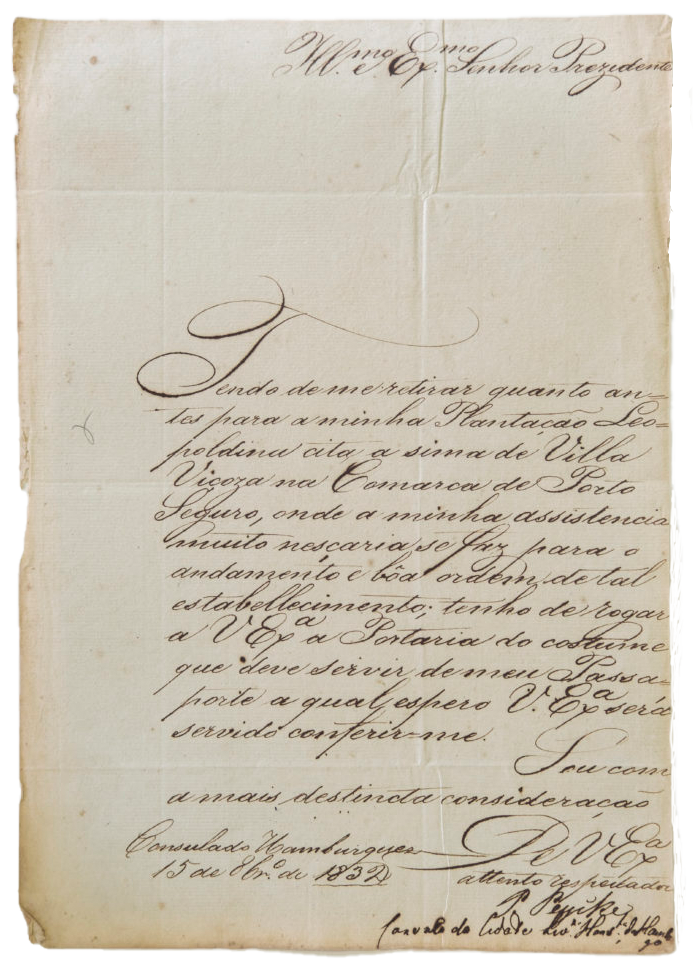

Letter to the president of Bahia

This letter is from the State Archives in Salvador da Bahia (Arquivo Público do Estado da Bahia (APEB), Seção de Arquivo Colonial e provincial. Governo da Administração). The heat and humidity have discolored the pages a bit. The letter is signed by the Hamburg Consul Peter (Pedro) Peycke, requesting to be granted the same privileges as the French and American Consuls.

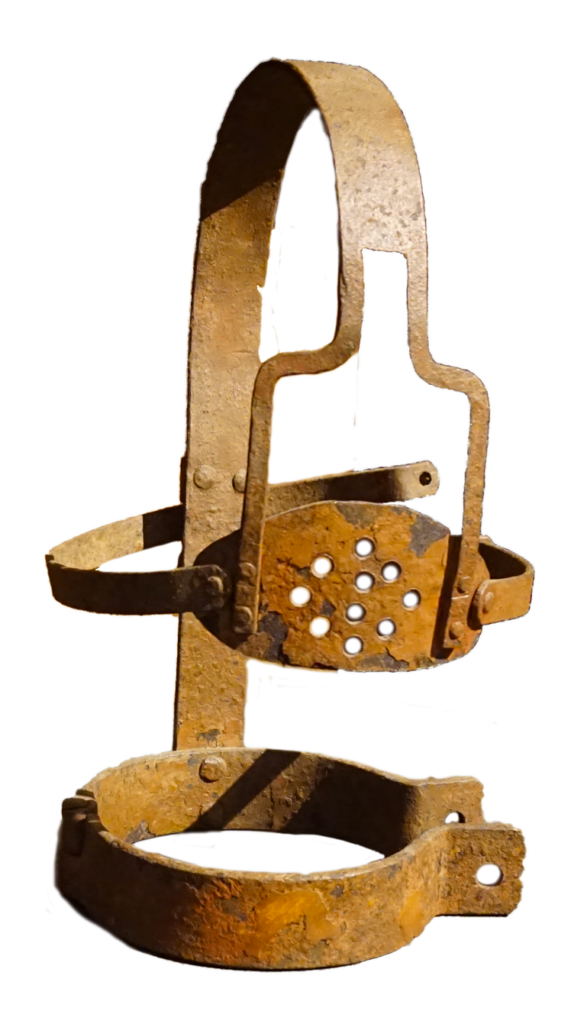

Gag

The iron mask was part of the brutal machinery of plantation colonialism. It was put on the enslaved as punishment and locked at the back. Such objects that testify to the dark side of modernity rarely appear in Western museums. The mask comes from the Museo Afro-Brasil in São Paulo, which was founded and directed for many years by the artist Emanoel Araújo. Araújo trusted the objects’ inherent power and presented the instrument of torture like an “autonomous” sculpture, not unlike a Picasso sculpture. He made a point of allowing the viewer to approach the object without prior understanding or explanation. Only on closer inspection – on the reconstruction of “what it actually is” – does the realization set in (and will probably have an all the more lasting effect).

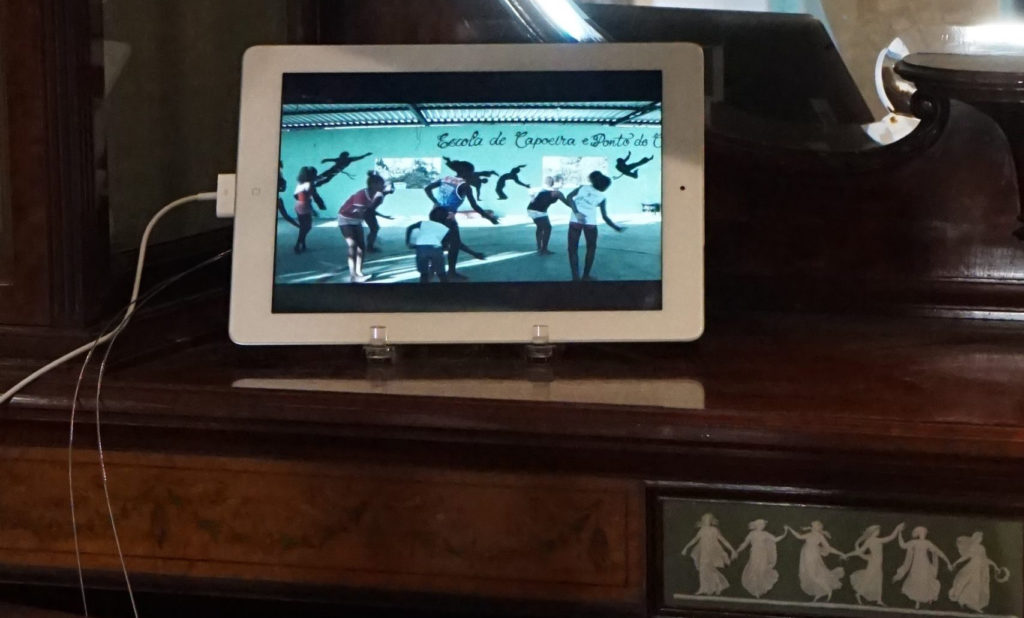

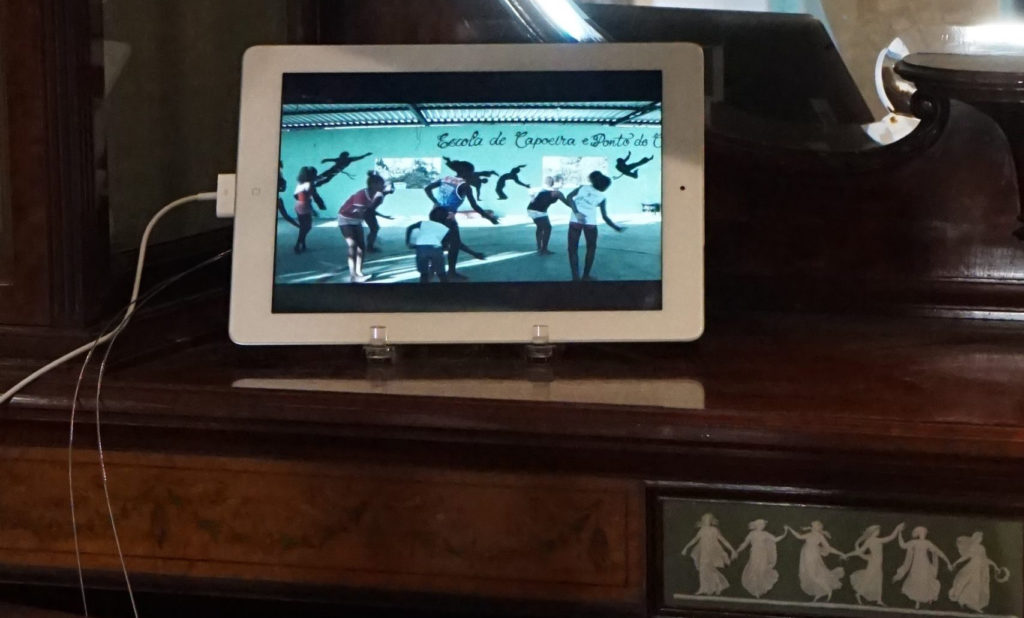

Capoeira

The Brazilian “Capoeira” was developed by enslaved people. Exercises disguised as a dance form were used for combat training.

Denise Bertschi: Helvécia, Brazil, 2017

Eyelet embroidery and excerpt of 3-screen HD video

Courtesy the artist

Am I not a Man and a Brother?

Josiah Wedgwood pushed the industrialization of English ceramic production, but was also an active member of the newly formed Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. To support the movement, he had William Hackwood, his most talented modeller, design a medallion. It shows a chained black man kneeling. Next to it a line reads, “Am I not a Man and a Brother.” Wedgwood had the medallion produced and distributed at his own expense. Ladies of high society wore it as a brooch, hat pin or necklace, gentlemen wore it with their snuffboxes.

Baroque door of a mosque in Porto-Novo

Enslaved people who managed to return to West Africa imported craftsmanship and formal aesthetic know-how from Brazil. Mosques, like the one in Porto-Novo (Benin), speak the language of the Portuguese Baroque.

St. Gallen Lace and Condomblé

Eyelet embroidery has a long tradition in Switzerland. With the Swiss mass emigration in the 19th century, the textile know-how migrated as well. When Denise Bertschi pursued her research in northeastern Brazil, she came across eyelet embroidery that was familiar to her from Switzerland. These embroideries decorated white robes in use during Candomblé ceremonies.

Beyond the real migration history of the embroidery, Bertschi’s work establishes an associative link – between the eyelet embroidery on the one hand and the perforated documents in tropical archives on the other. The cloth lists (in original script) the estate of a Swiss plantation owner. His estate in Bahia included 150 enslaved people.

Denise Bertschi: Helvécia, Brazil, 2017

Eyelet embroidery and excerpt of 3-screen HD video

Courtesy the artist

Hercules Sägemann Advertisement

Before the British cultivated rubber trees in Southeast Asia, natural rubber mostly came from the Amazon. In a telling contrast to the realities of rubber production, the poster shows a small indigenous family going about their work in an almost bourgeois, idyllic manner.

Fordlandia

The half-hour film transports us to the Brazilian jungle, with the camera patiently absorbing the overpowering environment. The images tell of the end of a fantasy called “Fordlandîa” – Henry Ford’s plan to grow and process the rubber he needed for his automobile production (for tires, hoses and seals) in Amazonia.

Bowl with ornamental loops

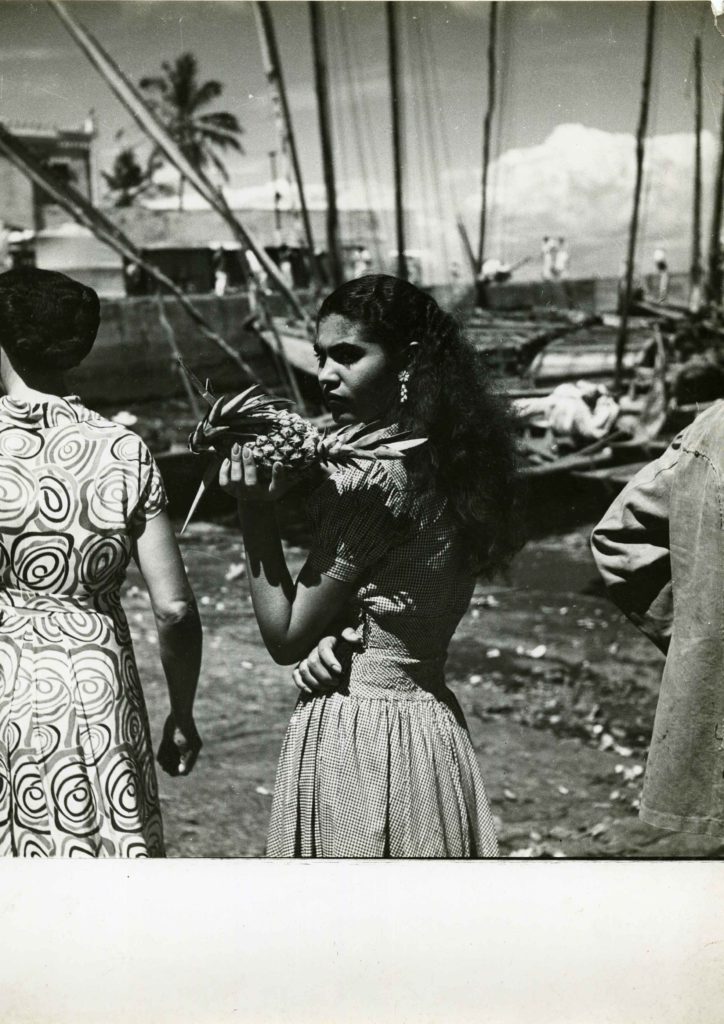

In the 1950s, Lina Bo Bardi, always attentive to shapes, bought everyday objects at markets in the Brazilian northeast. These included clay bowls, jugs, baskets or wooden spoons. The architect and designer recognized in these simple, functional objects the key to an independent Brazilian design.

Bahia, 1940ies

Squiggles, like those drawn by Pelé, can be found on clay bowls or clothing patterns in Bahia, Brazil, but also in West Africa.

Object No. 42

The football bears the signature of the Brazilian hero Pelé: a “P” with a squiggle. Pelé played for FC Santos, the port city from which Brazil ships its coffee around the world. Does the signature indicate Pelé’s affiliation with Afro-Brazilian culture?

The ball comes from the collection of the Docker’s Museum. This museum tells global history from the perspective of dockers. It was founded in 2010 by Allan Sekula with funds from MuKHA (Museum of Modern Art Antwerp).

Allan Sekula: The Dockers’ Museum, Object No. 42, 2010

Pelé signed football

Courtesy M HKA (Museum of Contemporary Art Antwerp), Antwerp

ARK Collective

In the 1960s, Japanese engineer Ikutaro Kakehashi developed the first drum machine equipped with a rhythm pattern generator. He was spoiled for choice with the Bossa Nova, as there were many versions circulating. In the end, Kakehashi chose the song “The Girl from Ipanema.” In doing so, he set the global listening habits to this particular sound pattern.

Team: Johannes Ismaiel-Wendt & Malte Pelleter Audio production: Sebastian Kunas Speaker: Sarah-Indriyati Hardjowirogo ARK (Arkestrated Rhythmachine Komplexities), Installation with 10 rhythm machines, 3 samplers, headphones and multichannel audio Courtesy the artists

Gag

The iron masks are a by-product of plantation colonialism. The plate in front of the mouth is to prevent the slaves from eating the sugar cane during the harvest. As in Haiti, sugar was the key source of European wealth in Bahia. At a later stage, coffee and cocoa took on greater importance. Such objects, which bear witness to the dark side of modernism, are usually not to be found in European museum collections.

Object No. 42 (The Dockers’ Museum)

The Brazilian football legend Pelé signed the leather ball with a stylized ‘P’. Pelé played for FC Santos, the team from the city with the largest coffee port. Does this signature signal Pelé’s affiliation with Afro-Brazilian culture? Or would this interpretation go too far, since the symbol itself is in fact very widespread?

The Pelé signed ball is part of Allan Sekula’s Docker’s Museum.