Maya Deren’s Haitian Rushes

Roger M. Buergel

0I/ In September 1947 I disembarked in Haiti, for an eight-month stay, with eighteen motley pieces of luggage; seven of these consisted of 16-millimeter motion-picture equipment (three cameras, tripods, raw film stock, etc.), of which three were related to sound recording for a film, and three contained equipment for still photography. Among my papers I carried a certificate of a John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship for „creative work in the field of motion pictures“ (as distinguished from documentary film projects), which was a reward for the stubborn effort that had been involved in creating, producing and successfully distributing four previous films with purely private and limited means and in the face of a cinema tradition completely dominated by the commercial film industry on the one hand and the documentary film on the other. Also among my papers was a carefully conceived plan for a film in which Haitian dance, as purely a dance form, would be combined (in montage principle) with various non-Haitian elements. I recite all these facts because they are evidence of a concrete, defined film project undertaken by one who was acknowledged as a resolute and even stubbornly willful individual.

Today, in September 1951 (four years and three Haitian trips later), as I write these last few pages of the book, the filmed footage (containing more ceremonies than dances) lies in virtually its original condition in a fire – proof box in the closet; the recordings are still on their original wire spools; the stack of still photographs is tucked away in a drawer labeled „to be printed,“ and the elaborate design for the montaged film is some – where in my files, I am not quite sure where.

This disposition of the objects related to my original Haitian project is, to me, the most eloquent tribute to the irrefutable reality and impact of Vodoun mythology. I had begun as an artist, as one who would manipulate the elements of a reality into a work of art in the image of my creative integrity; and I end by recording, as humbly and accurately as I can, the logics of a reality which had forced me to recognize its integrity, and to abandon my manipulations.

With these lines, New York filmmaker Maya Deren begins her treatise The Divine Horsemen: The Living Gods of Haiti (1953), which would remain the only conclusive testament to her experiences in Haiti.(1) Deren did not really touch the mentioned film, sound and photo material before her untimely death in 1961. While the film rolls totaling some six hours or longer have been stored in the Anthology Film Archives (in coffee cans labeled by Deren) and threaten to crumble into dust, both the sound reels and the negatives are currently housed at Boston University’s Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center. In other words, Deren’s magnum opus remains a powerful fragment, a construction site that – as Deren would have it – is, on the one hand, a testament to the failure of a decidedly modernist concept. Yet this failure is also rooted in a key moment that characterizes every transcultural experience. This key moment is the abyss over which the trans (well known to mean “over” or “between”) builds its more or less precarious bridges. Deren didn’t just look at this abyss in Haiti – she also created a literary monument to it in the last chapter of Divine Horsemen, in which she describes her own possession by a loa during a Vodoun ceremony.

Deren’s original concept, which took her to Haiti for the first time in 1947, was a film that would formally link rituals from a wide range of cultural contexts. The Caribbean Island was to be only one point of reference among others; Deren was also thinking about children’s games in Western societies, for example. In the artistic milieu of 1940s New York, Deren was not alone in her anthropological interest in the dramatization of cultural patterns in dances and ceremonies. Research on myths or, more generally, the influential force of unconscious cultural patterns played an important role in (exiled) surrealist circles, and mythical speculation (including the desire to create new myths) also influenced the artistic manifestos of Barnett Newman and Mark Rothko, for example. More significant for Deren was the research conducted by anthropologist and choreographer Katherine Dunham (1909-2006), for whom Deren worked as a secretary in the early 1940s. Dunham had studied forms of dance as a medium of religious release or possession within the Caribbean’s African Diaspora, and spent several months in Haiti in the mid-1930s to explore it.(2)

Another important influence for Deren’s Haiti project was her dialogue with Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson, two pioneering figures in visual anthropology. Both had systematically employed film and photography during their 1930s fieldwork in Bali.(3) Deren not only studied this Bali material in depth; Bateson was even willing to allow Deren to use this material for her aesthetic purposes. In fact, Deren drew her original inspiration from correspondence she had with Bateson in 1946 about the anthropological exhibition “Arts of the South Seas” at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. She writes:

As a matter of fact, you praise the exhibit precisely for the fact that each grouping of materials was true to the individual culture which it represented, at the same time that these groupings were so arranged in reference to each other as to create a „sensible“pattern which transcends

them all and even strengthened them, each in their individual terms as well. It is this concept of relationships upon which I wished to build my film…(4)

And more concretely in relation to the film project:

My problem, in a sense, was to build a fugue of cultures. But each voice must have its own melodic integrity. Consequently, my preoccupation with searching out a variety of cultures which had retained, in their own terms, their homogeneity was not based upon my personal interest in exoticism, but out of the need to have a variety of homogeneous structures which

would relate to each other in the film rather than blend into each other in the “melting pot” manner.(5)

Deren’s thoughts consequently revolved around how to exhibit foreign cultures, no matter whether in a museum or in a film context. She sought to capture what was special about each culture on the basis of comparison or, better yet, the communication of forms. As noted, Deren had no genuine interest in Haiti at first except as an example of “unified structure.” The fearsome complexity of Haiti’s political landscape became clear to her only after she had gone ashore with her eighteen crates and suitcases.

II/ In the late 15th century, Spain colonized a Caribbean island under Christopher Columbus, which they named Hispaniola. Spain officially ceded the western part of the island (present-day Haiti) to France in 1679 in the course of intra-European conflicts, and the colony was renamed Saint- Domingue. Saint-Domingue became a pilot project for the rather late onset of French colonial policy under Louis XIV, the so-called “Sun King.” In 1685, Louis XIV enacted Code noir, a comprehensive legal framework that introduced the concept of “race” in order to regulate the handling of slavery in the French colonies. In fact, the slave economy was seen as a prerequisite for the proto-industrial, enormously labor-intensive cultivation of sugar cane. Saint-Domingue soon accounted for 40% of Europe’s sugar consumption (and approximately 60% of European coffee) and became the richest colony in the world at that time. (Anyone who has ever wondered how Versailles financed itself now knows the answer.) The Atlantic triangular slave trade took 10,000 to 40,000 slaves per year from the West African coast to plantations on Saint Domingue. By the French Revolution (1789), the colony’s population included half a million slaves. By contrast, the number of white colonial rulers amounted to around 30,000 people; these were joined by a few tens of thousands of gens de couleur, people of mixed African-European origin who were allowed to exercise certain freedoms and own property.

After many smaller uprisings (mostly instigated by groups of escaped slaves) revolution erupted in Saint-Domingue in 1791. This revolution, which was partly inspired by the ideas of the French Revolution (but whose real catalyst was a Vodoun ceremony) registered as a global, epoch-making event: European thinking at the time did not account for the idea that slaves could free themselves. (6) While the Girondins in Paris welcomed the Revolution and French representatives accepted the abolition of slavery in 1793, the British tried to take advantage of the political confusion in Saint-Domingue starting 1794, and large parts of the white and mixed elite supported their occupation attempt.

It was only in 1800 that African-born military leader Toussaint Louverture successfully defeated the British. In 1802, Napoleon sent an army to Saint-Domingue to recapture the “Pearl of the Antilles.” The armed forces also included the Polish Legions. Although the French captured Toussaint Louverture, local troops triumphed in 1804 under their new leader Jean-Jacques Dessalines—not least because many European soldiers succumbed to yellow fever. The Polish Legions, or what remained of them, changed sides to join the new rulers. In 1805, Haiti finally declared its independence and gave itself a national flag by eliminating the middle, “white” stripe from the tricolor. In 1838, the French Republic demanded the present-day equivalent of US $19 billion for the official recognition of Haiti’s independence—a service of debt that completely crippled the already devastated country’s development and was only canceled in 1947. Today, Haiti is considered the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere; 75% of the population subsists on less than 2 US dollars per day.

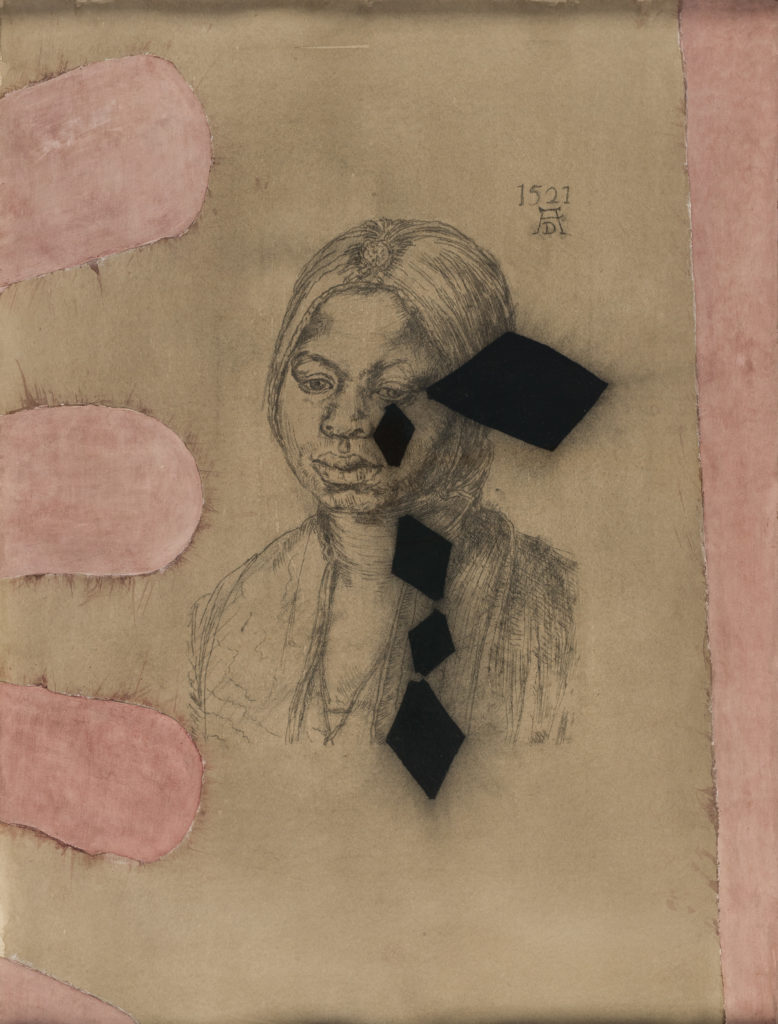

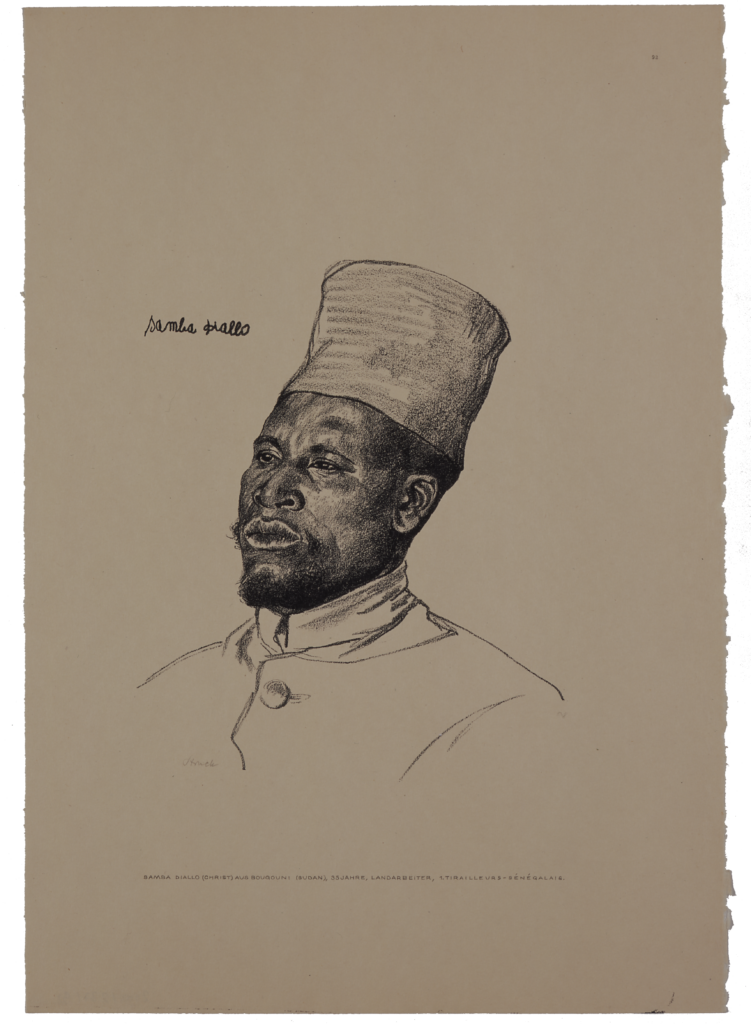

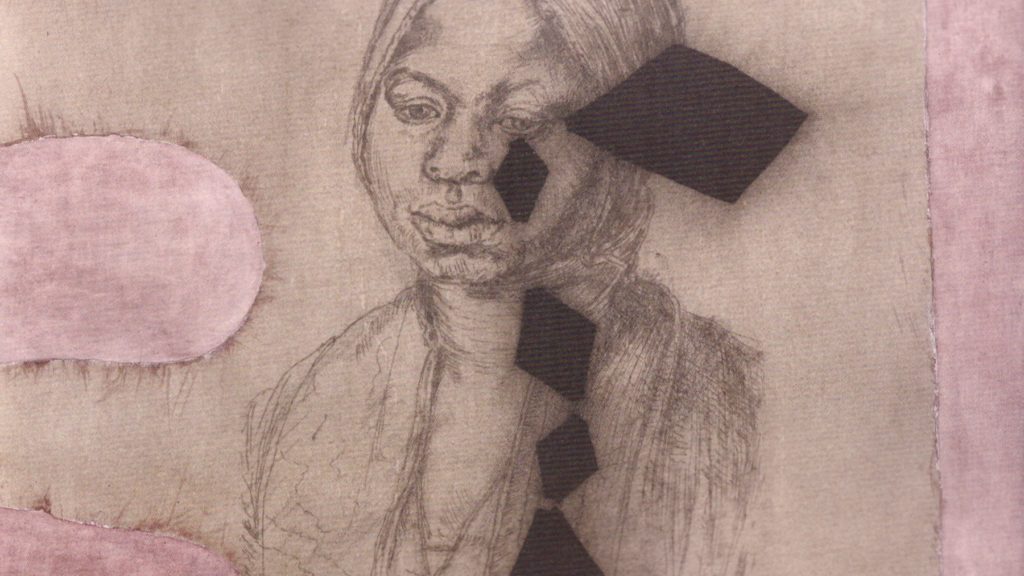

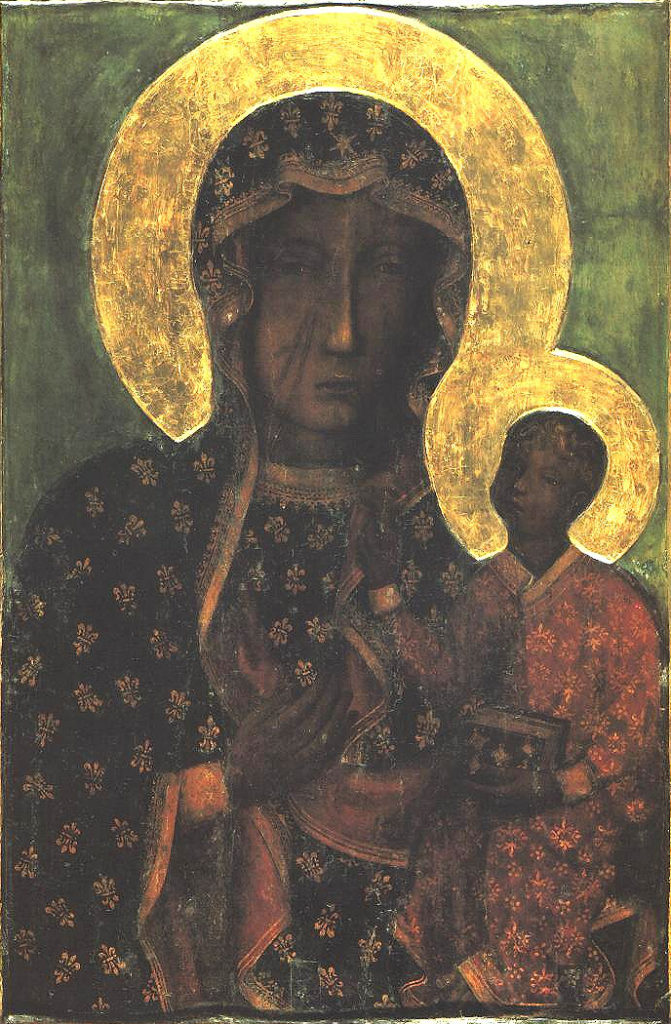

III/ This all-too-brief historical outline nevertheless shows that the country is anything but a “unified structure.” Forms of Vodoun were influenced by the traditions of various African ethnic groups, and these were also enriched with Roman Catholic and Masonic figures and symbols during the colonial regime. The Vodoun flag in our exhibition offers a good example of this kind of interconnection. Embroidered out of sequins, the image shows Erzulie Dantor on a golden background. Erzulie Dantor is an important figure in the Vodoun spirit world; she represents both motherhood and war. The bleeding heart in the design recalls icons of the Virgin Mary, but she also carries weapons. Representations of Erzulie have also absorbed a feature of the Black Madonna of Częstochowa: the Caribbean Madonna translates two deep notches in the lower left side of the face (sword blows to the Polish icon in the Middle Ages) in the form of facial scars. Lithograph reproductions of the Black Madonna of Częstochowa migrated to Haiti in knapsacks carried by Napoleonic Polish Legions and became part of the Haitian formal repertoire after the Poles switched sides.(7)

IV/ Deren instantly responded to the complexity of the situation she found in Haiti. The filmed material shows that she pulled away from every ethnographic perspective and gave herself over to the immanence of the ceremonies—to their rhythm and rules, but also their improvisational method. She used her personality to communicate with Haitian personalities at eye level. Rather than interact with them as a “participating observer,” as she knew from Bateson and Mead, she became an almost a-subjective, neither cognitive nor interest-driven element of an experiential context, albeit one with a camera.

1) Maya Deren, author’s preface to Divine Horsemen: The Living Gods of Haiti (New York: McPherson&Company, 2004 [1953]), 5-6.

2) See Katherine Dunham, Dances of Haiti (Los Angeles: UCLA Center for Afro-American Studies, 1983, 41-57.

3) See Sylvie Chakkalakal, “Margaret Meads Anthropologie der Sinne – Ethnografie als ästhetische und aisthetische Praxis,” in Zwischen Objekt, Text, Bild und Performance: Repräsentationspraktiken ethnografischen Wissens (Berlin: Panama, forthcoming. Chakkalakal did the research on Deren, Mead

and Bates on for this exhibition.

4) “An Exchange of Letters between Maya Deren and Gregory Bateson”, in: October, Vol. 14 (autumn 1980), 16-20. Deren’s letter dates from Dec. 9, 1946.

5) Ibid.

6) See Susan Buck-Morss, “Hegel and Haiti”, in: Critical Inquiry 26 (Summer 2000), 821-865.

7) See Sebastian Rypson, Being Poloné in Haiti: Origins, Survivals, Development, and Narrative Production of the Polish Presence in Haiti (Warsaw: Wydawca 2008), 82-90. Adam Szymczyk recommended this book to us.

We would like to thank Martina Kudláček both for her expertise and the Deren related material she contributed to this exhibition, as well as Anthology Film Archives and Jonas Mekas.