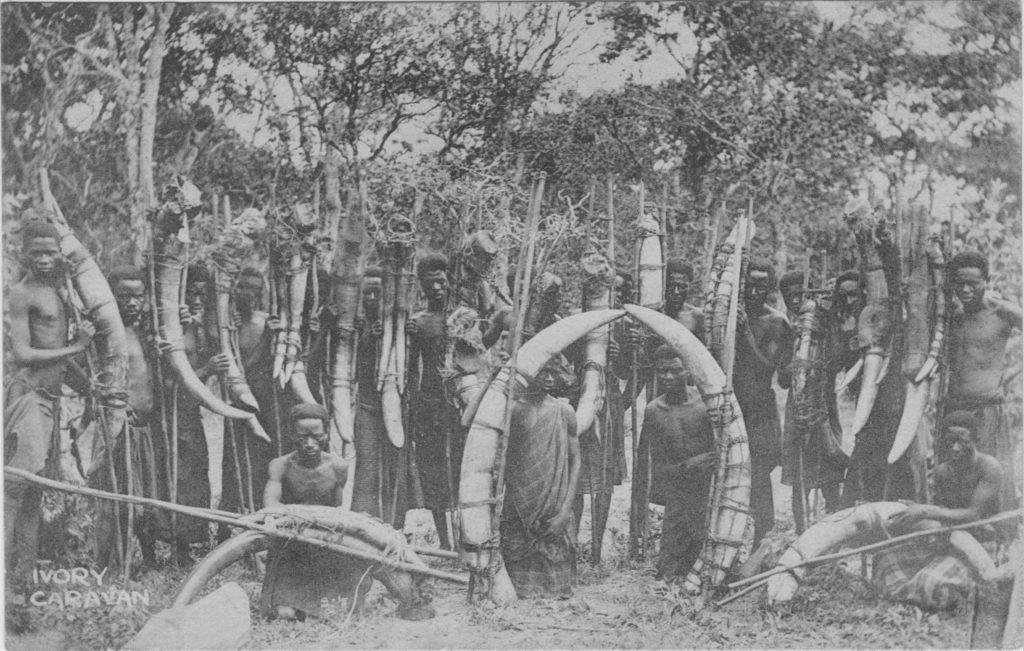

»Ivory Caravan«

The mass industrial processing of ivory in Europe brought with it that the elephant hunt on the African continent also became more costly and complex. The Congo Basin, where the herds had retreated, was difficult to access. In addition, it was a great logistical challenge to transport the tusks, which could be up to 4 meters long, to the central trading posts on the coast – for example, to Zanzibar.

“African” with elephant skin

The young man with the swiveling hips seems to come from hunting. Under his arm he wears an elephant skin that ends in a long trunk. The skirt and feather crown are reminiscent of the headdresses of the indigenous peoples of the Americas. For the modelers and painters of the Meissen porcelain manufactory around 1750, all these forms were available. To the courtly audience, they may have seemed plausible.

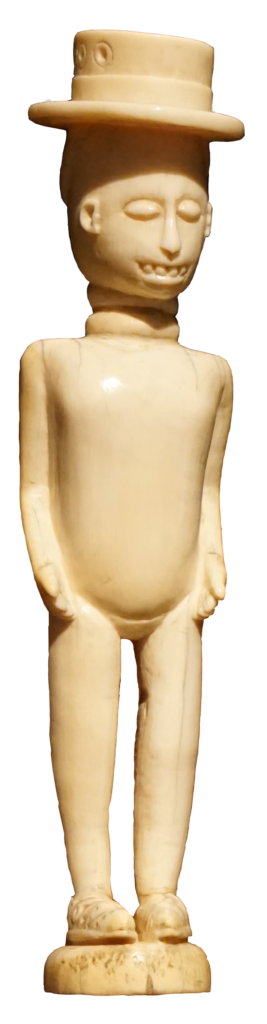

Figure of a Christian missionary

This ivory figure owes its origin to the high art of carving in Loango (now Gabon and Congo). The representation is a Christian missionary, apparently with filed teeth, whose hat, footwear and hairstyle are of European origin.

Cithrinchen

The “Cithrinchen” is a plucked string instrument, similar to the lute. It comes from the workshop of Joachim Tielke, a Hamburg instrument maker, and has more to offer than just the beautiful sound. The intricate ivory inlays depict Diana, the (Roman) goddess of the hunt, on the back. Arabesques wind around the body and neck of the fragile instrument.

Okimono in shape of an Egyptian

Netsuke belong to the finest of Japanese carving art. The small “buttons” were used to attach pouches and pipes to the belt of the kimono. In the Meiji period, the traditional garment went out of fashion. Men were required to wear suits in public.

After netsuke largely lost their function, carving artists began to look for other outlets. This ivory okimono is reminiscent of a Christian Madonna figure. However, the veil and bead make it clear that this is a fellachin, an Egyptian peasant woman. The “fellachin” was an Orientalist motif of the time. It circulated, for example, in photographs taken by the Cairo photo studio Lehnert&Landrock. There were however no real peasant women sitting as models in Cairo, but prostitutes or actresses dressed as peasant wome

Tusk

There are many pictures that Europeans have made of Africa. There exist pictures, too, of Africans aiming at the white man, but apart from exceptions such as Julius Lips, this view does not play a major role in the African departments of Western museums. Robert Visser went to the Congo in the late 19th century as a manager of cocoa and coffee plantations. He collected African artifacts, but was also an industrious photographer under often adverse conditions. One of his most significant collection items is the tusk of an elephant. Comparable to the Roman victory columns on which triumphal processions spiraled, there was an artistic tradition in Loango of carving narratives onto the tusks. These included genre scenes, as well as scenes of chained enslaved people, animals, and more. This tusk shows Visser himself as he positions his boxing camera. Next to it are depictions, such as a couple in front of a hut, that go back to Visser’s photographs.

The tusk is now part of the collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African Art

Ivory warehouse

In Joachim Tielke‘s time, ivory was rare and thus valuable. This was to change when the Europeans systematically came to grips with the elephant in order to process its tusks into billiard balls, piano keys and the knobs of walking sticks. A look into the warehouse of Heinrich Christian Meyer’s factory, called “Stockmeyer,” gives an idea of the scale of the butchery.

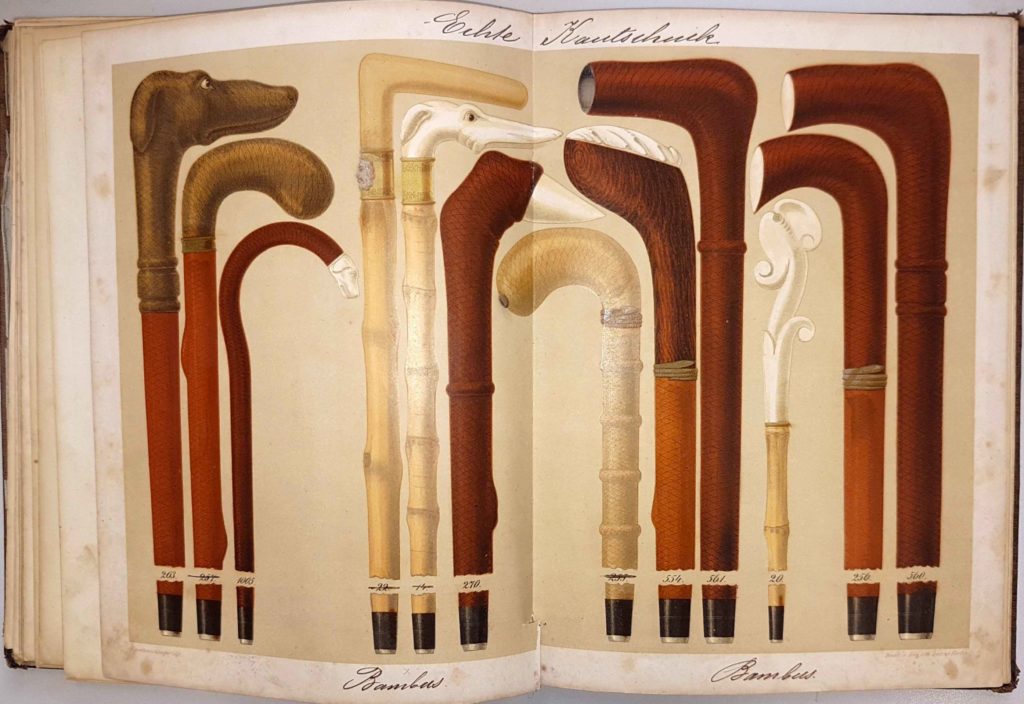

Walking-Sticks

Hans Christian Meyer – called “Stockmeyer” – made walking sticks. His starting materials were whalebone, bamboo, sugar cane and later rubber. Soon, ivory knobs were also part of Stockmeyer’s product range. The entrepreneur was a pioneer not only in the use of novel, “exotic” materials from overseas. In 1837, he was one of the first major industrialists in Hamburg to use steam engines and provided health insurance for his workforce.

The small ivory bust by Ludwig Lücke (1717-1789) shows the Hamburg merchant and publisher Johann Hinrich Dimpfel. Dimpfel was chairman of the Chamber of Commerce, and his daughter was married to the German poet of “Empfindsamkeit” [sensitivity], Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock.

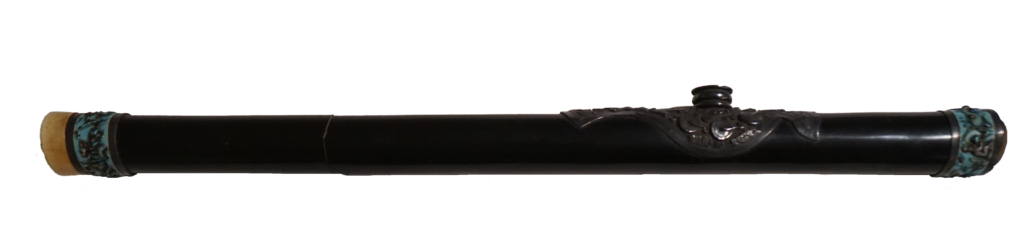

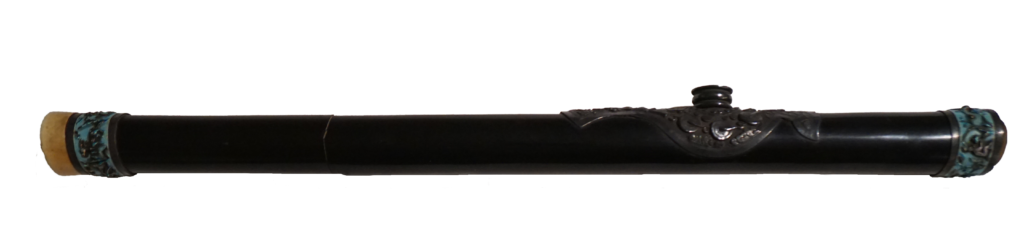

Opium pipe with ivory mouthpiece

China always wanted cash (usually silver) for silk, tea and porcelain. There were hardly any Western products for barter. One exception was opium, a narcotic that enjoyed great popularity among the elite. When the British imported more and more opium from their crown colony India, the emperor put a stop to the trade. Western “free traders” in Canton (the port of entry) ignored this import ban. When Chinese troops then seized and destroyed entire cargoes of opium, the British declared this a cause for war. They sent their navy to attack Canton and other coastal cities. This began the First Opium War (1839 – 42), which ended with a Chinese defeat. As a result of the war, the Western powers were able to establish trading bases (so-called “treaty ports”) on Chinese territory and dictate the terms of trade according to their own convenience and advantage.

The opium pipe is a souvenir from the Boxer Rebellion. Like the pewter beaker, it belongs to the household of the great-grandson of a North German naval officer (Oberbottelier).